Translating plays into movies is no easy task. Dating back to the days of Alfred Hitchcock's Juno and the Paycock, Hollywood has a long history of turning plays into stilted films that leave one wondering why the producers didn't just film a live stage performance. But that isn't to say cinematic adaptations of plays are inherently doomed. On the contrary, the likes of 12 Angry Men or Casablanca show both that it can be done. But these films also show that there isn't a one-size-fits-all strategy for properly adapting plays into movies. Every single play has certain qualities that can or cannot translate well into movies. You've gotta dig into what made these stories so captivating in the first place and figure out the unique ways only movies can enhance those qualities.

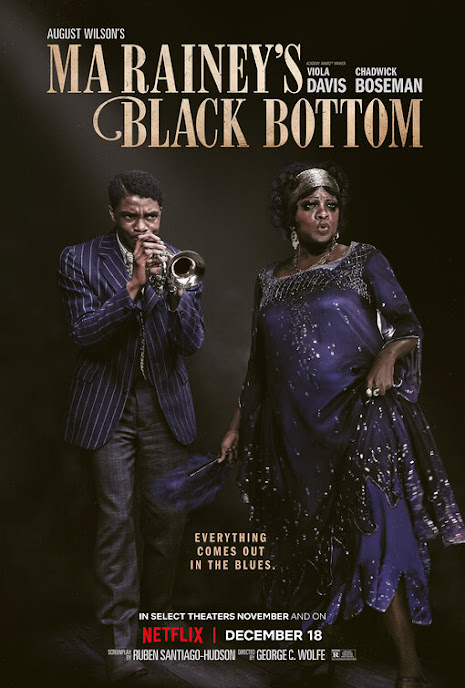

Another movie that proves it isn't a fool's errand to adapt plays into movies is Ma Rainey's Black Bottom, an adaptation of August Wilson's 1982 play of the same name. Adapted by Ruben Santiago-Hudson and directed by George C. Wolfe, this feature concerns the real-life blue singer Ma Rainey (Violas Davis), as she, in the twilight years of her career, tackles a new album in a Chicago recording station. Accompanying her is her band, which consists of guitarist Cutler (Colman Domingo) and trumpet player Levee (Chadwick Boseman). Perhaps the only person with as pronounced of a personality as Ma Rainey is Levee, who has his own ambitions as a musician and isn't keen to compromise with anyone to fulfill those dreams.

Wilson's work is rightfully acclaimed as some of the most impactful productions to ever grace Broadway. But how does something like Ma Rainey translate into a film? Impressively well, as a matter of fact. You don't have to be a rocket scientist to figure out how that happened. Both Wolfe and Santiago-Hudson have made their own adjustments to the story, including changing the setting from the winter to the sizzling hot summertime. Some of these tweaks, like the pay-off to Levee constantly charging at a locked door, have been done to take advantage of the opportunities afforded by a movie. But the duo also know that sometimes, things that aren't broke don't need to be fixed. In this case, what made the Ma Rainey play so compelling isn't compromised in the translation into a new medium.

It's easy to imagine Ma Rainey falling prey to the distracting elements that plague other film adaptations of play, chiefly the act of engaging in sweeping camerawork to make the whole production feel "epic" rather than "stagey". Wolfe and Santiago-Hudson, though, are confident enough to maintain the intimate scope of the original show, with much of the story taking place in either a recording stage or a basement rehearsal space. Keeping things so self-contained isn't just good because it's faithful to the source material. It also works for Ma Rainey on its own artistic terms. Someone who's never even read or seen Wilson's work will still be gripped by Ma Rainey's intimate nature.

One of the advantages of this restrained sensibility is that Ma Rainey's digressions outside of this space a real sense of purpose. A scene of pianist Toledo (Glynn Turman) reflecting on the larger experience of Black Americans while shots of Black Chicagoans sitting in window sills and standing against lamposts flash across the screen is effectively stirring. Meanwhile, keeping everything confined makes the bubbling tension between all the characters believable, particularly with regards to everyone's rapport with Levee. As both the audience and the other characters become trapped with Levee, a guy who starts out as a cocky musician with golden shoes becomes someone far more layered and damaged.

The complexities of Levee as a character are reflected in two extended monologues brought to life through a Chadwick Boseman performance that cements why Ma Rainey is content to keep its scope so limited. When you've got actors this good, you don't need a thousand locations. Just Boseman talking about a traumatic childhood experience that informed how he treats white people, that's all you need. In this scene, Boseman communicates a lifetime of anguish, trauma, determination, scorn, and so many other emotions, all swirling around inside one volatile human being. Boseman utterly throws himself into a performance that's unlike anything else he's ever done. Even with all the hype generated by his work, I still wasn't prepared for how breathless I'd be left by Boseman in Ma Rainey's Black Bottom.

Inhabiting the titular role of Ma Rainey, Viola Davis also reaffirms her acting bona fidas with a turn that's a walking-talking paradox. A woman that's simultaneously fearless in demanding what she wants yet also tormented by her current status as an artist, you can't rip your eyes off Davis, especially with how much torment she communicates in her eyes. Davis and Boseman alone make Ma Rainey's Black Bottom worth watching. The fact that the production also delivers so much else (including a great supporting turn from Colman Domingo, impressive costume work, and thoughtful commentary on the struggles of being a Black artist) only cements Ma Rainey's Black Bottom as something exceptional.

How do you turn a play into a film? In the case of Ma Rainey's Black Bottom, you lean heavily on the qualities that made the play work in the first place. Emotionally urgent performances and an intimate scope have defined so many of Wilson's best plays. Now, in the hands of actors like Davis and Boseman and a director like Wolfe, such qualities are alive and well in a cinematic format. As richly human as it is heartbreaking, Ma Rainey's Black Bottom is a play adaptation done oh so right as well just good filmmaking on its own terms.

No comments:

Post a Comment