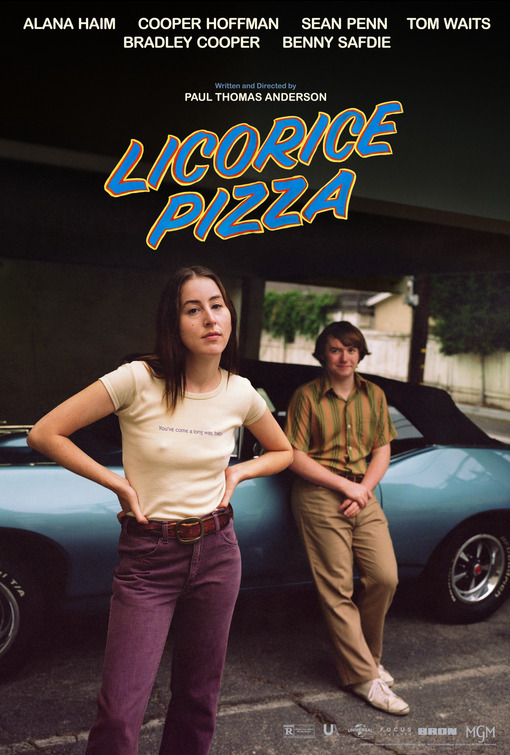

The works of Paul Thomas Anderson have dealt with some heavy topics. But there's always been bursts of comedy in these productions that suggest how adept this filmmaker is tickling your funny bone. Even the often bleak There Will be Blood features that hysterical moment where a fight between Daniel Plainview and Eil Sunday ends by cutting to a dinner table where Sunday is sulking while covered in dirt and mud. Anderson's sharpness as a director has come in handy to make these moments as memorably humorous as they are. With his newest feature, Licorice Pizza, Anderson gets to make a whole movie that's just light-hearted gags and hangout vibes. It's a mold that departs from, say, Hard Eight, but it's also a mold that suits the filmmaker nicely.

Alan Kane (Alana Haim) and 15-year-old actor Gary Valentine (Cooper Hoffman) met in an innocuous enough manner. It's a picture day at Valentine's High school and Kane is a 25-year-old helping organize everything. Valentine becomes immediately smitten with her and he insists that he take her out on a date. For obvious reasons, Kane s disinterested in the proposition. From there, the duo can't stop hanging around each other, with the pair opting to work as business, rather than romantic, partners on a variety of businesses. The haywire nature of the 1970s means that there's something new around every corner, from a gas shortage to the antics of producer Jon Peters (Bradley Cooper), to ensure that the lives of these two crazy kids will never get boring.

The concept of making a movie with kid leads where the adults are the immature one is not novel. Plenty of other features, especially ones targeted directly at youngsters, have gone down this road. But Licorice Pizza makes this approach feel fresh again simply by adding a quasi-tragic air to its execution of this concept. Watching adult figures in roles of great authority like actor Jack Holden (Sean Penn), performer Lucy Doolittle (Christine Erbersole) or even Richard Nixon (seen only through archival footage on television) act even more selfish than the 15-year-old protagonist of Licorice Pizza is a stark reminder of what it means to be a "grown-up".

Valentine and Kane are constantly pursuing avenues that they think will automatically grant them the wisdom and security that they imagine comes with adulthood, that can cure their insecurities as adolescents. But none of the grown-ups seen in Licorice Pizza seem to have everything together. If anything, they've gone mad with power, fueled by insecurities they can never wrangle. We've all seen movies centered on kids where the grown-ups are just immature buffoons. But Licorice Pizza's twist on this concept is to emphasize the consequences of all that buffoonery, to linger on how hard to is to grow up in this kind of world. The incompetence of the cops or the president, fueled by vanity specific to adulthood, can ruin your whole life in the blink of an eye.

Then again, maybe the immaturity of the adults is to just allow for more amusing comic situations for the two leads to interact in, but it's a testament to Licorice Pizza's quietly impressive screenplay that it could be interpreted in this manner. Like so many great comedies, Licorice Pizza can be appreciated as either something deep, rich with sociopolitical commentary or just as something you put on the TV as a reliable feel-good pick-me-up. Like so many films that inhabit the latter category, the success of Licorice Pizza can be measured by just how many lines of dialogue get stuck in your head afterward. Everyone be wary of me throughout January as countless comedic witticisms from this screenplay will be a regular part of my lexicon to an annoying degree.

Anderson's script isn't just chock full of funny lines of dialogue, it's also impressively committed to a hangout vibe that serves the characters and atmosphere perfectly. Rather than handicapping the lives of Valentine and Kane with traditional three-act-structure problems, their existences ebb, flow, and go on about complicated paths, just like real people. It's just wonderful how Anderson can pause things at will to allow a runaway truck or waterbeds to suddenly become the focus of things. In reality, you never know what's going to suddenly consume your life. The laidback storytelling of Licorice Pizza captures that part of daily existence beautifully.

Taking such a chilled-out approach to things also gives the central actors plenty of opportunities to shine, especially Alana Haim in the film's breakout performance. In her first-ever acting role in a feature-length production, Haim comes alive as a firecracker that isn't afraid to speak her mind in any situation. Some of the best moments of Licorice Pizza are just Haim going scorched Earth on everyone around her, especially one unforgettable scene where she lays into her sister's. Haim is a riot in Licorice Pizza, ditto for Bradley Cooper in a small but memorable role that allows him to channel Eric Andre energy as his version of Peters will say and smash anything at a moment's notice.

Though very distinct projects in terms of tone and underlying themes, Licorice Pizza most reminded me of The Master in terms of prior Paul Thomas Anderson directorial efforts. Both are period pieces that aren't afraid to eschew conventional narrative norms in favor of just following around two people and their ever-complicated relationship. In both cases, keeping things so lean and streamlined is an ingenious move and makes for cinema you can't stop thinking about. Going in a more lighthearted direction for Licorice Pizza doesn't zap the substance out of Anderson's work. It just unleashes new ways for this filmmaker to impress, including in his dynamite choices for the film's soundtrack. Hooray for a 1970s period piece choosing unorthodox needle drops instead of the same old tracks we've all heard a thousand times before!