It's so much fun to finish a movie and then immediately know "Oh, that's gonna become one of my favorites."

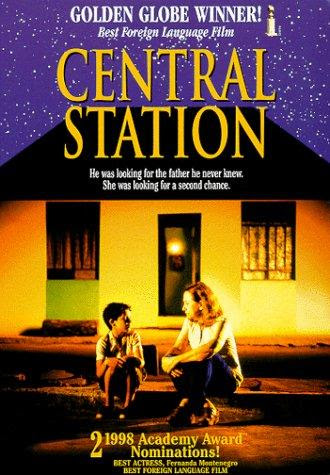

That doesn't happen very often, but it's just what I experienced with Central Station just last week.

Central Station begins with Dora (Fernanda Montenegro) making her living writing down letters that people dictate to her at a local train station. She's instantly hostile for the people she writes for and even refuses to mail some of the letters she pens. Her life gets upended when Josué (Vinícius de Oliveira) enters the picture. After his mom is abruptly killed by a speeding bus, this youngster has nowhere to go. After initially ditching him with strangers for cash, Dora proceeds to take the kid on a road trip to reunite him with his father. With minimal cash to their name and no consistent ride by their side, it's going to be a miracle if they ever get to their destination.

We've all seen movies with crotchety adults getting mixed up with precocious youngsters and, wouldn't you know it, both parties learning some valuable lessons through their interactions. Central Station is technically part of this subgenre, but it's up there with Paper Moon as an example of this strain of cinema at its apex. Rather than constantly remind you of other movies, Central Station makes warm and fuzzy cinema feel fresh out of the box again. It's clear now that the likes of St. Vincent were chasing this movies coattails, hoping to capture a fraction of Central Station's intellect or filmmaking ingenuity.

Part of what makes the screenplay by João Emanuel Carneiro and Marcos Bernstein work so well is its commitment to rendering its two leads as real people. For Dora, this means allowing her to be an especially messy person, with no concern over whether she's "likeable" or not. She's supposed to capture relatable angst over everyday existence, not be a model citizen. She also doesn't have a ham-fisted origin story always dictating her actions, we only get brief glimpses (like her recalling a story of when she ran into her absent father as a teen) into the events of yesteryear that molded her into who she is. For his part, Josué also behaves in a manner that's rooted in reality, with all the imperfections of an actual child rather than the tidy precociousness of a 1990s sitcom kid.

Plus, it's all captured with such impeccable visuals courtesy of director Walter Salles and cinematographer Walter Carvalho. An early piece of camerawork where Dora's conversation with another adult man at her work station, captured through a low-angle shot in a peephole to simulate Josué's point-of-view, sets the standard for the kind of thoughtful camerawork that works its way into the entire feature. I especially love the way Salles and Carvalho use empty space once the main duo of Central Station gets into more rural territory. A shot of the two characters sitting in front of this mountain-like object while a sprawling sky hovers above them is such a striking image that immediately communicates how outmatched Dora and Josué are in their quest to find the latter character's dad.

Combining such tenderly thoughtful visuals with a whip-smart script makes Central Station one of the very best road trip movies as well as something that accomplishes one of my favorite things in any piece of art. Specifically, Central Station is able to sneak up on you with how much you've got invested in these characters. The seemingly throwaway interactions Dora and Josué have shared throughout the film gradually add up to Dora coming out of her shell, a development that hit way harder than I expected when I started watching this movie. By the time she's writing letters again, but this time being more conscious of the humanity of the people she's putting pencil to paper for, I was astonished with how well Central Station had set up and pulled off Dora's totally organic character arc!

It's only fitting that a movie like Central Station that can pull off character beats like those would wrap up its runtime on a note that opts for realistic imperfections rather than a tidy resolution promising happy endings for all. In the end, Dora and Josué go their separate ways. The latter character will wait with his older siblings for their dad to maybe return, and Dora will go back to her old life. Uncertainty hangs over both of these characters, but thanks to the time they spent with one another, they're a little more capable of tackling whatever comes next. Neither they nor the audience needs to know what happens next. They just need to hold on to memories of everything that just happened.

This bittersweet but utterly perfect conclusion reminded me of the works of Mike Mills, specifically C'mon C'mon and 20th Century Women in terms of its complicated depiction of who helps shape our adolescent selves. The fact that a random lady like Dora could have such a profound impact on Josué even reminded me of this quote from 20th Century Women:

"I don't know if we ever figure our lives out. And the people who help you, they might not be who you thought or wanted. They might just be the people who show up."

Thank God for the people who show up and thank God for movies like Central Station.

No comments:

Post a Comment