“You are all going to fucking die.” Those are the first words uttered by Garfield in The Garfield Movie. To make the impact of that evocative phrase all the more profound, his proclamation is delivered against a black screen. This all-consuming void gradually shifts to a blue color as Garfield’s voice over continues to ponder the nature of mortality. “We’re all destined to die,” Garfield continues as the blue hues grow more vivid, “and capitalism only accelerates this inevitability.” In an obvious homage to Derek Jarman’s Blue (a film fellow animated kids movie Sing 2 also homaged recently), these words are delivered against a vacant screen dominated by only one color. There is nothing to distract us from Garfield’s disdain for existence and the status quo. From the get-go, The Garfield Movie uses the titular feline’s famously surly attitude to inform bold visual choices.

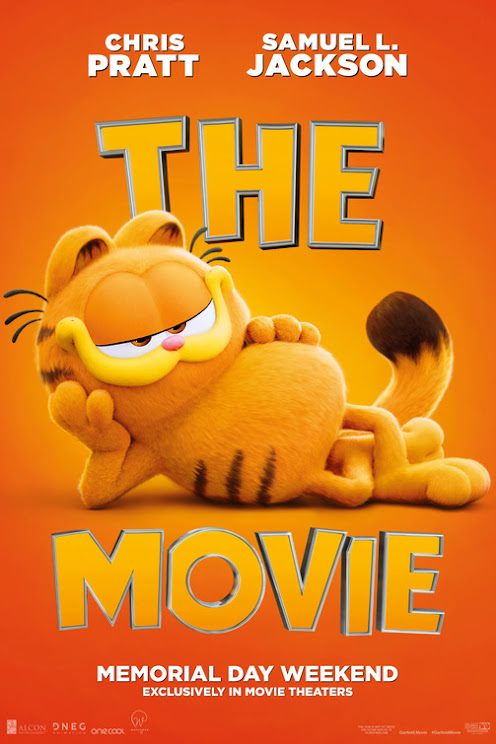

Eventually, director Mark Dindal cuts away from this vacant screen and allows viewers entrance into two portions of Garfield's life. These various points of his existence are explored in a non-linear fashion in the screenplay by Paul A. Kaplan, Mark Torgove, and David Reynolds. The first of these sections explores Garfield (Chris Pratt) in 1978 as an idyllic younger feline with hopes of changing the system. The second concerns Garfield in 2024, his cynicism baked in even deeper. Jon Arbuckle has died due to an opioid overdose. Odie has become a right-wing commentary hero thanks to his incel views. Pooky enlisted in the U.S. military right after 9/11 and perished overseas. All the cross-cutting across time reinforces the reality that Garfield is alone and how much he's lost over the intervening decades. His passion in 1978 especially resonates as tragic as the 2024 version of this cat grapples with compromising his beliefs in the name of a quick paycheck from the U.S. government. Specifically, the FBI wants intel on protestors that Garfield is inadvertently close to.

Will Garfield's original class consciousness carry the day? Or will he get to buy all the lasagna he can dream of thanks to selling his soul?

The best sections of The Garfield Movie thrive on an avant-garde nature that echoes the subversiveness of Garfield in his 1978 days. The soundtrack, for example, only plays songs by the bands Korn, Thousand Foot Krutch, and Toad the Wet Sprocket, often in a distorted fashion. Contorting the tunes in this fashion lends them an alienating quality that jars fascinatingly with their underlying familiarity. We recognize the lyrics...but why is the overall sound so disorientingly unusual? It's a sonic parallel to the feature's unique vision of Garfield, which translates the cantankerous nature of the critter created by Jim Davis into something much darker and more rooted in reality. Meanwhile, the digressions into abstract imagery contain countless striking visuals that really send home how divorced from reality Garfield is. He randomly succumbs to these visions that somehow have more comfort than the terrifying reality he's entrenched in.

It's also fascinating to see how Dindal and company reimagine classic Garfield characters in a context that will resonate with modern family viewers. Most notably, Arlene makes an appearance here after being defined as just "Garfield's pink girlfriend" in the comics for decades. Here, Arlene is radically overhauled into a cocaine-snorting lesbian communist played with vocal gusto by Rachel Sennott. This interpretation of Arlene is already a winner for how much it subverts expectations and plays to Sennott's strengths as an actor. However, it's also an ingenious maneuver since Arlene now functions as such a vivid contrast to Garfield. Whereas this orange tubby is slow-paced and snarky, Arlene has all the energy of a hummingbird and has sincerity oozing out of every orifice. An evil version of Odie, a morally ambiguous vision of Nermal, and a shell-shocked incarnation of Lyman also upend viewer conjectures of what a Garfield movie "should" look like.

These departures from the source material are a welcome treat in The Garfield Movie. Similarly impressive is a filmmaking style relying on quiet lengthy single-take shots that echo similar images in the works of Chantal Akerman and Apichatpong Weerasethakul. These prolonged visuals may irritate some viewer, but I appreciated how they let the viewer marinate in sights like Garfield scarfing down lasagna or Arlene passed out on the kitchen floor after a coke bender while a Toad the Wet Sprocket ditty gently plays in the distance. Rendering these moments in static shots that last for ages really gives us a window into the tormented lives of these animals and humans. Garfield may hate Mondays, but moviegoers are bound to love this artsy style of cinematography.

Unfortunately, The Garfield Movie, like so many summer tentpoles, eventually succumbs to traditional impulses of mainstream entertainment. After juggling its non-linear avant-garde impulses so well for so long, the third act focuses on Garfield beating up adversary Nermal. True, Garfield comic fans will undoubtedly find some emotional catharsis in seeing Garfield brutally slam Nermal into the pavement for ten consecutive minutes (accompanied by disturbingly realistic sound effects). However, such easy emotions feel underwhelming compared to the atmospherically ambiguous proceedings that previously dominated The Garfield Movie. You're supposed to feel good watching Garfield proclaim "I am a God, kiss my furry feet you cucks". However, Dindal's filmmaking thrives best when it leaves you unsure of what you're supposed to be emotionally experiencing. These concessions to standard filmmaking norms betray the transgressive mold-breaking artistry that defined the original Garfield comics penned by Jim Davis. This cat didn't just become famous because of ubiquitous merchandise. He became so enduringly well-known thanks to his ability to speak to the proletariat and shatter the mold of how comic strips operate.

Unfortunately, the choice to have Chris Pratt play Garfield is a microcosm of how The Garfield Movie struggles to properly straddle the line between its artsier impulses and it's adherence to mainstream sensibilities. Credit where credit is due, Pratt throws himself into the role and channels Kelsey Grammer's big Republican-skewering speech in "Sideshow Bob Roberts" by lampooning his own right-wing impulses in some of Garfield's line deliveries. An offhand quip from Garfield about how "maybe gays should just not be so in your face!" or "I heard Jordan Peterson say vaccines cause autism" show that Pratt has a sense of humor about how the public perceives him. Unfortunately, such meta-lines gradually build up over time to ensure that Garfield can't stand on his own two feet as a character. He's an extension of Chris Pratt, a movie star that The Garfield Movie seems to have cast just for a bunch of guaranteed publicity. It's nifty to see Pratt poking fun at his own image by thrusting himself into lines like "it sure would be nice if somebody would demolish historical Los Angeles buildings for selfish purposes!" However, that very same quality undercuts the standalone qualities of a performance that's supposed to anchor The Garfield Movie. Stunt casting, alas, lets this version of Garfield down.

When The Garfield Movie channels its arthouse influences just right, it harkens back to those formative days of the character. Not only that, but the greatest sequences carve out a new creative vision for this pop culture staple. Thanks to the most impressive artistic accomplishments of Dindal and the other artists, the very idea of what Garfield "can be" has expanded to an exciting degree. Still, a final scene of Garfield making out with Richard Nixon in Heaven reinforces how much The Garfield Movie eventually loses its way. Quiet contemplations of how hope can curdle into cynicism eventually give way to extreme examples of "shocking" the viewer. Sure, it's a little shocking to see Odie shooting people with a gun in a mainstream movie or hearing Nermal recite an entire monologue from Elmer Rice's Dream Girl before driving his Cybertruck into a brick wall. But these moments seem to be trying too hard to be transgressive. The Garfield Movie gets so much power in that opening sequence with just a blank screen and its main character's narration.

When the feature leans on that kind of restraint, it really makes Jim Davis proud. When The Garfield Movie gets too convinced of its transgressiveness, though, it's best to just send this feature back to U.S. Acres.

No comments:

Post a Comment