"It's important to record, because then you have a weapon," - Bitaté

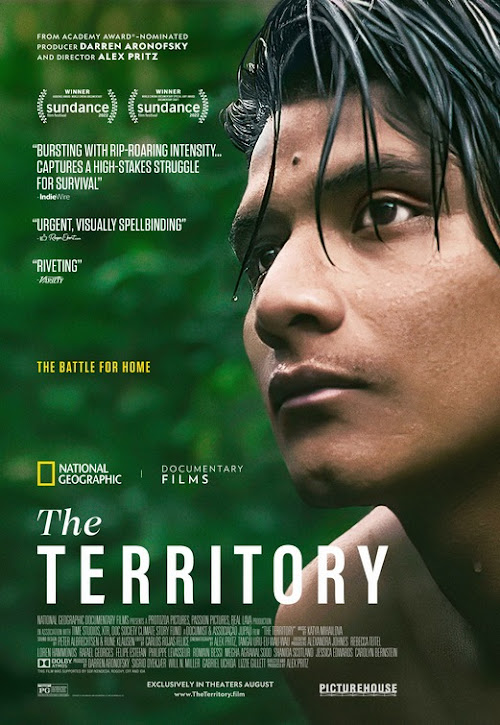

Within the Amazon rainforest, the indigenous Uru-eu-wau-wau people have carved out a home for themselves. They want nothing more than to just be left alone, to not have to fight for the very act of existing. Unfortunately, "invaders" are constantly cutting into their rainforest to build new houses and cities. With government officials in Brazil, namely the President of the country, Jair Bolsonaro, refusing to help indigenous populations, deforestation and its effect on marginalized groups are only bound to increase. As captured on-camera in The Territory, activists like Neidinha Bandeira and members of the Uru-eu-wau-wau will do whatever it takes to protect these lives and this culture, even though the odds against them keep growing more and more momentous.

The Territory does not immediately conjure up memories of other documentaries dealing with deforestation or hardships facing the Amazon rainforest. Instead, what it most immediately echoes is Harlan County U.S.A., a deservedly iconic documentary that chronicled rebellion from everyday people in real-time. The determination of those striking coal miners crusading for their humanity seemed to emanate off the screen, as did the obvious dangers they faced in their battles. Director Alex Pritz evokes such captivating filmmaking by putting viewers right in the middle of the land the Uru-eu-wau-wau call home as well as the nuances of their everyday lives. What is now being dismissed by intruders as just a stumbling block to monetary gain is the focal point of the camera in The Territory and those stakes lend a sense of urgency to the proceeding.

This immersive quality to The Territory is only enhanced in its final half-hour, where the on-screen indigenous subjects get to really control what gets filmed. In the wake of the COVID-19 pandemic, Bitaté, a lifelong member of the Uru-eu-wau-wau, decides it's time that he and his people have more say over how their lives are framed in the media. Bitaté and his allies proceed to chronicle the everyday lives of the Uru-eu-wau-wau extensively, with this footage making it into the final feature. The very existence of such footage serves as a refutation of the concept of an Ethnographic film, or a documentary of non-Western people by Western filmmakers. The sense of othering that can come from this style of filmmaking is fascinatingly absent from the images captured by cameras operated by indigenous hands. It's a subversive approach to documentary cinema that also results in some of the most intimate and memorable images of The Territory.

Combining different types of camerawork captured from varied perspectives lends a subtle sense of scope to The Territory without making the film either too bloated in scale for its 86-minute runtime or feel like it would be better served in a longer-form narrative. Fritz even finds time to interview the workers who've taken it upon themselves to start chopping down the wood that belongs to the Uru-eu-wau-wau. In their words, there's a quiet tragedy to their motivations that these interview participants don't even realize. In feeling desperate enough financially to harm this sanctioned territory, they're demonstrating how capitalism (a political and economic system constantly championed by Bolsonaro) turns members of the working class against one another. Their problems with monetary issues lie with powerful government forces, not indigenous populations just trying to survive. This discrepancy doesn't make the "invaders" sympathetic. However, it does make them fascinatingly oblivious examples of how capitalism leads people to demonize marginalized groups rather than focusing on fixing larger systemic problems.

The fact that the interview segments with the Invaders in The Territory carry so much underlying power speaks to how quietly detailed this entire documentary is. Pritz has created a consistently layered film rich with details, including in its depiction of the varying perspectives and personalities lying within the Uru-eu-wau-wau community. This subtly thorough nature even extends to how this film is captured in a 2:39:1 aspect ratio. An unusual (though, as the likes of Boys State show, not unprecedented) framing choice for a documentary, going this route allows The Territory to occupy the same visual style as classic narrative films that have offered up harmful depictions of indigenous populations. Just as Bitaté is reclaiming the media image of his people by filming his friends and neighbors, so too is The Territory reclaiming visual facets of cinema by using them to tell a story that's about humanizing native lives.

Thankfully, The Territory maintains its thoughtful nature through its very last frame. Any concerns that the feature would resolve itself in a tidy fashion that makes it seem like the hardships of the Uru-eu-wau-wau are in the distant past are proven wrong by the feature's final melancholy scenes. This includes an unforgettable moment where activist Neidinha Bandeira sits in a pond as raindrops fall around her. It's an evocative image on its own, but it gets even more powerful through her short bursts of narration. Here, she comments, in voice-over, that "I don't have a lot of time left, but I will use what I can to bother those who hurt the Amazon." In her words, we hear a quietly poignant reflection on the finite nature of existence. These lines also convey a recognition that the crusade for this land and its people is bigger than one person, not to mention a fighting spirit that defines the very heart of the powerful documentary The Territory.

No comments:

Post a Comment