CW: Discussion of suicide ahead

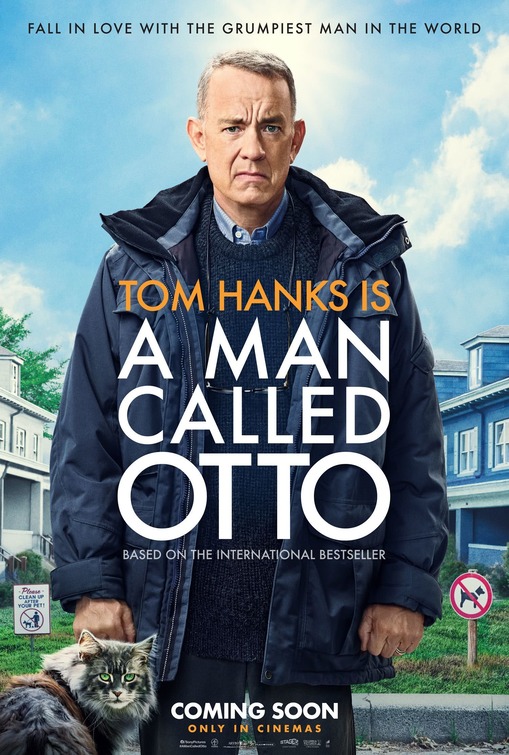

While it's always good to see Tom Hanks in anything, A Man Called Otto can't help but feel, on the surface, like a strange and even downright unwelcome visitor. A remake of the Swedish film A Man Called Ove, itself an adaptation of the famous novel of the same name by Fredrik Backman, A Man Called Otto belongs to that treacherous subgenre of English-language remakes of foreign-language movies. For every The Departed, a proper way of translating an international film to a quality standalone motion picture, we get a dozen or so of these kinds of remakes that add nothing to the films they're adapting. They merely feel like ways to cash in on familiar brand names, regurgitate stories told better elsewhere, and quietly reinforce the idea that the only movies worth watching are the ones told in English.A Man Called Otto's worst elements do echo the infamous shortcomings of many English-language remakes of foreign-language movies, namely in being less subtle and daring than the film that inspired it. But shockingly, writer David Magee and director Marc Forster have concocted a touching drama with A Man Called Otto that isn't breaking any new ground in its form but does prove affecting more often than not.

Otto (Tom Hanks) is a cantankerous old man who begins A Man Called Otto ready to kill himself. Just as he's ready to put a noose around his neck, though, he sees that new neighbors Marisol (Mariana Treviño) and Tommy (Manuel Garcia-Rulfo) are making a mess in trying to park their moving van. A stickler for the rules, Otto leaves his suicide attempt behind and begrudgingly helps the duo properly park their automobile. From here, Otto continues to engage in various suicide attempts, all of them stemming from the anguish and hopelessness he feels over the recent loss of his wife. However, Marisol, Tommy, and other members of his neighborhood, including a homeless cat, keep inserting themselves into Otto's life and giving him reasons to stick around just a little while longer.

Director Marc Forster has shifted gears across many genres over the years (including blockbusters with World War Z and Quantum of Solace) but A Man Called Otto sees him returning to a mold he's often occupied: tearjerker dramas. Even his foray into a live-action adaptation of animated Disney characters, Christopher Robin, adhered to the melancholy and poignant nature of many of Forster's forays into this field, such as Finding Neverland or The Kite Runner. A Man Called Otto nicely fits into this well-trodden mold. Much like with Christopher Robin, Forster isn't blazing new trails with Otto but still makes an effective weepie.

What proves especially moving here is one of the most unique visual facets of A Man Called Otto compared to the original Swedish film. This time, the flashbacks to Otto's past that occur whenever this character attempts suicide are now more directly tied to the present-day world. Occasionally, the camera will cut back to Otto murmuring portions of words he said in the past while the older and younger versions of Otto will sometimes find themselves inhabiting the other one's world. Time is a flat circle for Otto, tragedy has made everything seem like it's happening at the same time. These visual details poignantly suggest how consumed by the past Otto has become while adding a distinct visual flourish to the proceedings.

Those flashback sequences give A Man Called Otto its pathos while much of the entertainment value of feature comes from its performances. Having "America's Dad" Tom Hanks play a cranky old man may seem like obvious stunt casting, but the reliably strong Hanks proves so good in the role that it's impossible to complain about his presence in the role of Otto. Shockingly, outshining even Hanks in terms of the performances here is Mariana Treviño. An incredibly compelling performer with a sharp sense of comic timing, she proves incredibly gifted at holding her own and then some in sequences where her bubbly character has to go toe-to-toe with A Man Called Otto's disillusioned protagonist. Just watching Hanks and Treviño spar is enough to justify A Man Called Otto existing beyond being a way for someone to wring more money out of the A Man Called Ove book.

While A Man Called Otto rises above expectations in some key respects, it also, unfortunately, succumbs to several problems that plague many major American movies meant to function as a tearjerker. For one thing, subtlety isn't the strongest suit of either Magee or Forster and that problem comes to a head in the biggest emotional moments of Otto. Conceptually devastating sequences depicting Otto's most tumultuous moments from the past are undercut by needle drops that use ham-fisted lyrics to beat you over the head with the scene's purpose. Surely Thomas Newman's score could've carried these scenes. Similarly, the third act is weighed down by several clumsy instances of characters, namely Otto, practically turning to the camera when they flatly explain their major character defects before saying how they're improving as a person. That kind of overly obvious dialogue makes it hard to invest in these character arcs.

The home stretch of A Man Called Otto could've used more of the finer subtle details that make the excellently-realized flashback sequences so moving. But even when it lives up to the reputation of major American melodramas being all tell and no show, A Man Called Otto still gets a boost from some great performances and its low-key depictions of people bonding with one another. Sometimes my heart gets won over by simple things like Otto gradually bonding with endearing neighbors like peppy jogger Jimmy (Cameron Britton) or cyclist Malcolm (Mack Bayda). I'm still not sure if we needed an English-language remake of A Man Called Ove, but if we had to get one, then A Man Called Otto is a solid take on the material.